The thought of getting a mammogram can be daunting for some, so during a Breast Cancer Awareness month, Wellington journalist Virginia Falloon took the opportunity to experience it for herself. Her experience is a great perspective that many women may relate to.

I'm lucky, I know.

So many women in my life haven't felt the sweet, knee-weakening relief of hearing a doctor say "your breasts are healthy, your mammogram was fine".

Unlike them, I left the hospital as light as the proverbial feather, safe in the knowledge that at least one part of my body was safe, at least for now.

I know I'm lucky, and it seems terribly unfair that, mostly, luck has everything to do with it.

"In my early 40’s, I'm now in the age group targeted by experts battling the cancer that kills more than 600 New Zealanders a year, a cancer that nine women are diagnosed with every day."

While the national screening programme provides free mammograms every two years for women aged 45-69, the Breast Cancer Foundation recommends a yearly test for women between 40 and 49, then two yearly after that.

The reasoning behind the early screening is it's in our 40s that the disease will develop more quickly than it does as we age, and simply, early detection means early treatment.

If I'm following the foundation's advice I'll be paying for my own tests for the next three years. Will it be worth it? I reckon.

Although doctors warn a clear mammogram doesn't mean any other suspicious symptoms of lumps, creases or dimpling in the breast should be ignored, the test is a bloody good insurance policy.

"My family doesn't have a history of breast cancer – we drew the short straw on heart issues instead – and mistakenly, I thought that meant I was pretty safe. It doesn't."

Before Pacific Radiology's lead mammographer Suz Gibbs got down to wrangling my breasts into the x-ray machine at Wellington's Bowen Hospital she told me I had been living under a false sense of safety.

"Only about 20 per cent of people with breast cancer have a familial history of the disease. That's why the screening is so important."

The actual examination is ridiculously quick and easy. It doesn't hurt, it isn't embarrassing and it's over in about four minutes.

Each breast is placed between plates and scanned in two different positions: it's this part I've heard is the most painful but, other than the unflattering sight of my flat breast, it's a doddle.

Gibbs says women can experience varying degrees of discomfort during the exam but most react like I did, with an impressed "is that it?".

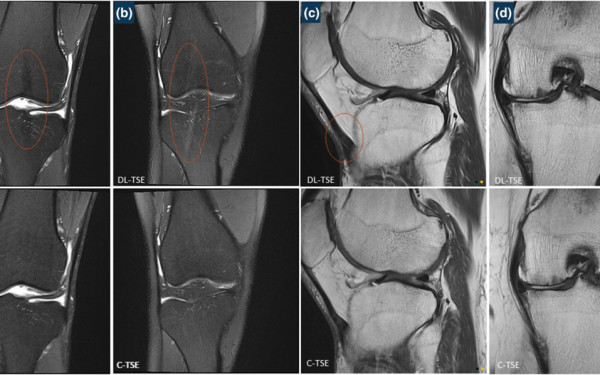

Usually results are sent to the patient's doctor but again I'm lucky and once dressed follow Gibbs into the darkened room where images of my breasts are displayed in jaw-dropping detail on computer screens.

Showing me a 7mm lymph node as en example of what the test can pick up, the radiologist says breast cancer gets a bad rap.

"But what you don't hear is how treatable it is, especially found early."

I'll be back in a year and if something is found then, it will hopefully be early and the treatment should be easier, the outcome better.

Luck might have everything to do with it but I can give it a hand.